Contemporary Jewelry – what is it?

Array

Array

If you ask a passer-by in the street if they know what jewelry is, they will probably answer ‘yes’. People have become aware that jewelry means a pretty object serving as an adornment to the outfit and a person. It is not as simple as it may seem, though.

In the Dictionary of Fine Art Terms we can read that:

Jewelry, small jewelry and goldsmith’s articles, used as decorative items worn for personal adornment – both body and outfit. It is mainly made of valuable materials (noble metals: gold, silver, platinum, gemstones, ivory) and decorative ones (nacre, etc.), decorated with various techniques and characterized by artistic execution – in this meaning also the ornaments of indigenous, primitive people with colorful stones, horns, bones, etc. Jewelry has been known in all historical periods and in all cultures which defined the social role of jewelry and a pool of basic forms. The starting point was usually a function of an object, particularly evident in the objects used to decorate clothing (safety pins, buckles, pins[…])[1]

In my opinion this definition covers only a part of jewelry closely associated with the goldsmith’s traditions. Currently, not only is the definition of jewelry changing, but also its function, which was once confined only to decorating. Contemporary Jewelry, also known as Modernist Jewelry, has gone far beyond the craft, becoming virtually another discipline of art, a tool to express the author’s statement.

In another suggested definition we read:

Jewelry can be not only the item of clothing but also of the interior. It is often an independent sculptural object, but paired with the silhouette of a human or serving as a prop of the show – a part of the author’s statement. Jewelry is often an artistic commentary on important events for the artist. Formerly, on the other hand, it represented a clear message. It provided information about marital status, number of children, it even was a means of payment. [2]

A definition suggested by Bruce Metcalf tells us that [3]:

…jewelry falls between sculpture on one side and garments on the other. Like sculpture, most jewelry consists of a physical object that has its own discrete existence. Some jewelers clearly intend their work to be viewed isolated from the human body. But unlike most sculpture, jewelry is also inextricable from the presence of a living person: most jewelry is made to be worn, or imagined being worn. So, like garments, the site of jewelry is the body. But unlike garments, jewelry is rarely made to protect people from heat, cold, precipitation and the gaze of our neighbors. There are, however, certain limitations concerning jewelry: it is its relatively small size (so that the object can be attached to the body), the weight, impracticality of some media (these requiring e.g. the use of electronics or other technologies – and hence difficulties in their processing – still it is difficult to imagine jewelry with a build-in TV). As for the latter, a lot is changing with the development of technology and access to some of the solutions is growing, which broadens the possibilities for artists. [4]

In order to understand why there are so many discrepancies in the definition of the concept of jewelry, we should go back to the end of the nineteenth century, when the first harbingers of change in this area appeared. Contemporary Jewelry is very internally diverse and in some ways represents the cultural phenomena and social attitudes of its time.

The twenty-first century is a period of the industrial revolution which resulted in the emergence of new materials and construction technologies. It revised architects’ approach to the design, and thus, completely changed the field of architecture. Initially, these materials were used in the construction of less prestigious venues such as factory halls, viaducts, bridges and railway stations. Later, inter alia, thanks to the Chicago school that first decided to take such a step, technological innovations have contributed to changes in the architecture of towns.[5] Modernism stood out from the decorativeness, the tradition for decades equated with different variations of historicism. It glorified function and simplicity of form –which was justified. Primarily, the function and proper communication were significant in the design of buildings intended to serve as banks, office buildings, department stores, airports or ammunition factory. The development of modernism in architecture was delayed because of the time and money needed to complete the project. The changes in the jewelry progressed much more quickly, but in a way analogically. The creators of contemporary jewelry decided to distance themselves from the typical conventions of craft and extremely decorative ornaments. They were tired of jewelry that is just pretty and does not represent deeper ideas.

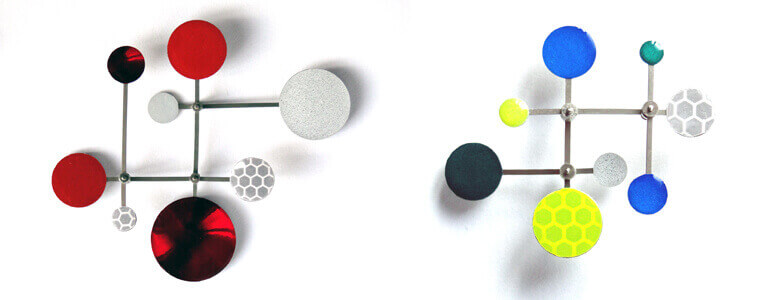

In 1946, the Museum of Modern Art in New York organized an exhibition titled Modern Handmade Jewelry, which included design studies of goldsmiths such as Margaret De Patta and Paul Lobel, and jewelry modernist artists such as Alexander Calder, Jacques Lipchitz and Richard Pousette-Dart.

Alexander Calder’s jewelry was very strict in form, made with the use of primitive technique, in a way reminiscent of the spirit of improvisation and creativity. It was a turning point in the history of American contemporary jewelry and a strong contrast with the work of Margaret De Patta, trained under the tutelage of Professor László Moholy-Nagy [8] Bauhaus school in Chicago.

Combining jewelry and sculptures was not unfounded. These are areas quite related: both use similar techniques, materials and artistic forms. The main element that differs them is the scale and the fact that the sculpture has always comprised in the concept of a higher, pure art, while the artistic jewelry was considered as something disgraced by money, very specifically defined by utility.

It is vital to be aware of the difficult situation in which contemporary jewelry makers were, and why it had such a form and not another. People involved in the creating this type of objects usually had professional education, a certain sensitivity, knowledge of, inter alia, the composition and a very strong need for creating, also art for the art’s sake. It turned out, however, that in order to express themselves artistically, they had to turn in the direction of another, foreign to them, pure art discipline. I will leave the matter for speculation how a person who is wholeheartedly associated with experiments in the goldsmith’s workshop can feel when they are pulled out from their place of work and forced to change somewhat their profession. It is not surprising that the artists decided to rebel and create what the heart told them to, without paying attention to the critical voices from the crowd. And the voices were loud – because apart from the people who could not accept the contemporary jewelry as art, there were craftsmen brought up in the old school of Art and Craft’u, who mocked modernist jewelry which by experimenting with form and materials, often moved away from traditional jewelry and goldsmith art. Jewelry has never developed in one direction only. At the same time there were outstanding masters of the craft in the world, the designers trying to smuggle to an outdated set of designs something new and fresh, which had its own form of artistic expression and artists trying to see how far you can separate jewelry from the man, change its shape and the type of the materials used.

The art historian, Blanche Brown, writes:

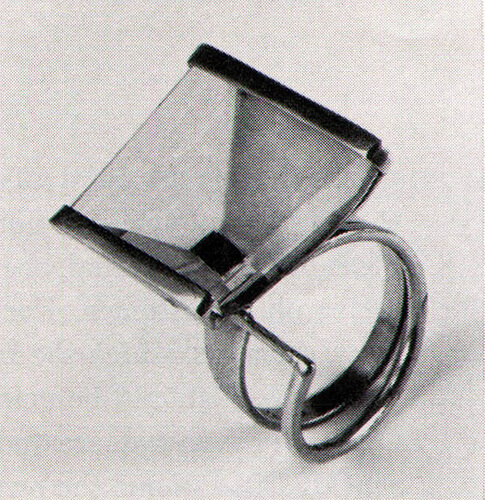

About 1947 I went to Ed Wiener’s shop and bought one of his silver square-spiral pins . . . because it looked great, I could afford it and it identified me with the group of my choice – aesthetically aware, intellectually inclined and politically progressive. That pin (or one of a few others like it) was our badge and we wore it proudly. It celebrated the hand of the artist rather than the market value of the material.[9]

Jewelry turned into a completely new form. It became the object of goldsmith – which subsequently later on and in the extreme variation of Contemporary Jewelry will not have too much in common with precious materials. And yet, in one of the first definitions of jewelry mentioned here, it is stated black and white, that the jewelry that is not made of precious materials ceases to be jewelry. What is more, parallel to the Contemporary Jewelry, the phenomenon of costume jewelry appeared, mass-produced, cheap, made from new materials and closely associated with the wave of pop art. The borders began to blur – what is art and what is not? Does the same object, made of plastic, take on a new meaning depending on the context? Who is an artist – and who does not have the right to be called one? I believe that the answer to this question can help aesthetics theory proposed by Arthur Danto and described in detail in his book, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace. I encourage you to familiarize yourself with this book. At the same time, I hope that via this text, I was able to bring Contemporary Jewelry phenomenon closer to you, so that the works of artists that will appear here, will meet with greater understanding.

Bibliograhy/Footnotes:

1. Słownik terminologiczny Sztuk Pięknych, Warszawa 2002, p. 47

2. Andrzej Boss, Biżuteria wczoraj i dziś, „Granice sztuki globalnej rzemiosło, design, sztuka”, p.76

3. American artist, actively involved in the world of contemporary jewelry makers, began his artistic career in the ‘70s of the XX century

4. Bruce Metcalf, On The Nature of Jewelry, http://www.brucemetcalf.com/pages/essays/nature_jewelry.html [online 23.01.2015]

5. Anita Włodarczyk – Kulak, Maurycy Kulak, O sztuce nowej i najnowszej – główne kierunki w sztuce XX i XXI wieku, Warszawa – Bielsko – Biała 2010, p.25

6. Angela J Daniel, A History Of Contemporary Jewellery, http://ezinearticles.com/?A-History-Of-Contemporary-Jewellery&id=724158 [online 23.01.2015]

7. Franciszek Zastawniak, Złotnictwo i probiernictwo, Warszawa 1957

8. László Moholy-Nagy – Hungarian painter, photographer, designer, filmmaker, theorist, a professor at the Bauhaus

9. Brown Blanche, Ed Wiener to me, „Jewelry By Ed Wiener”, Fifty/50 Gallery, 1988, p. 13

Tell us, what do you think about it